da Monica Guerra | Mar 11, 2020 | altre pubblicazioni

Tre inediti da Nella moltitudine

(Il Vicolo, 2020)

Anteprima editoriale

su Atelier

qui il link per leggere l’articolo

nella moltitudine

verrà, dicevi, la sera di piombo

parole o tarantole verrà e poi zittivi

zittivi il passo e il seme

dentro la carne il boccone

gravido del dissenso

il delitto della profezia

nella voce l’anima si spacca

l’attesa è un tempio

in cui si fa la fame

da Monica Guerra | Gen 10, 2020 | altre pubblicazioni

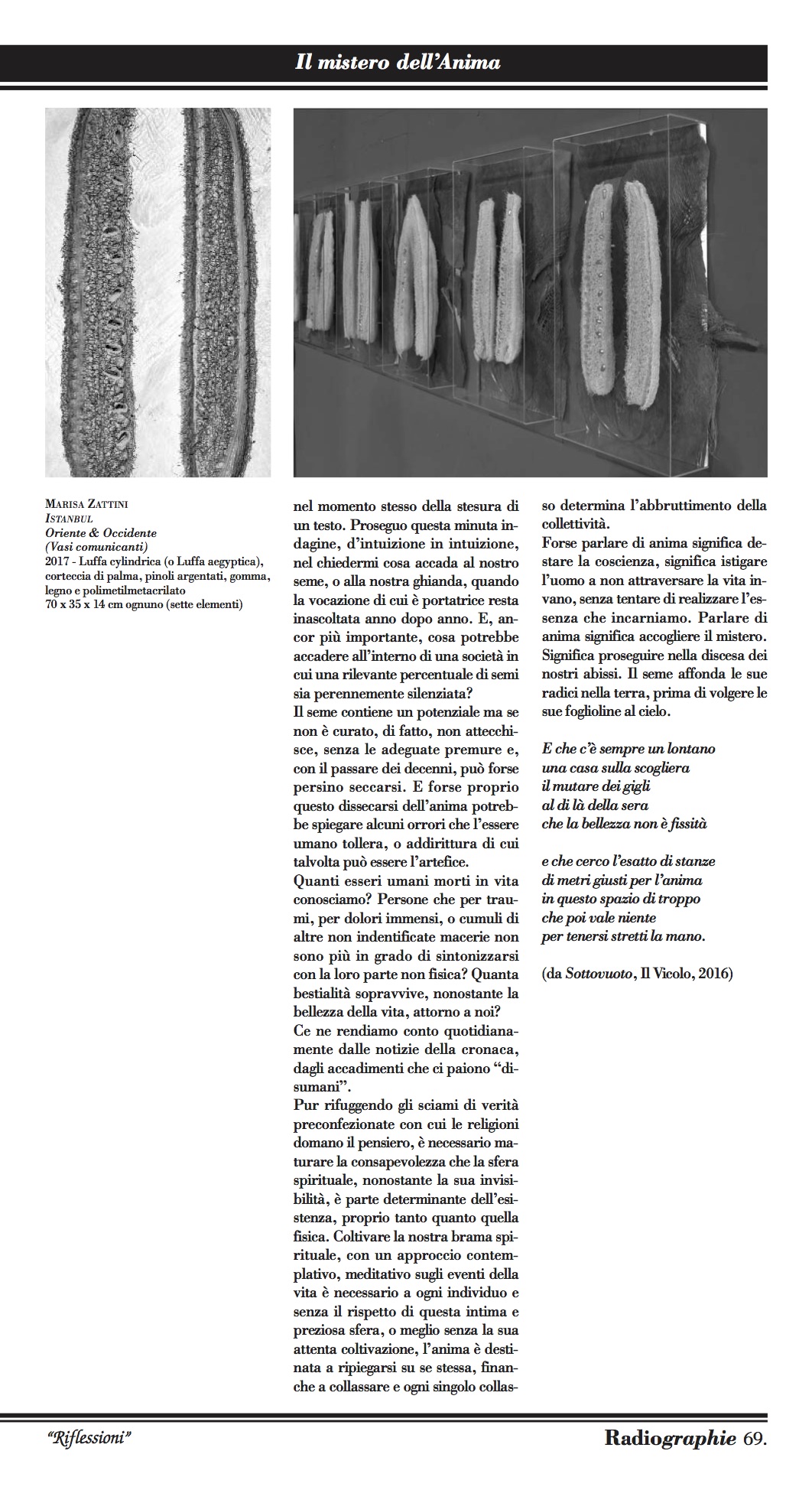

En el umbral (Uniediciones, 2019)

En el umbral (Uniediciones, 2019)

Traduction Antonio Nazzaro

Es la bitácora de una larga despedida en un umbral que es una demarcación de un confín, de la esperanza de que todo pueda salir bien, de un happy ending inexistente. El relato de una pérdida por parte de quien se queda.

Cuando nos saludamos en el umbral porque alguien está a punto de partir, auguramos un buen viaje y un buen retorno. Si es cierto el no retorno ya desde un comienzo, se busca de todas las maneras posibles detener a quien está por irse, dándonos la ilusión de lograrlo durante los altibajos de un largo periodo de enfermedad. Y quien es capaz lo escribe, como hizo Monica. La sensible ternura, junta al dolor que sobresale desde el prólogo, viene al final, acercándose al sentido amargo de la realidad, pero con una mirada nueva, directa y ya sin el temor de aminorarse. Todo esto hace de un poemario atrayente e interesante. Es la fuerza de ponerse a prueba, de rebasar y quedar, utilizando esta “Errante paloma imaginaria”, grande e incomprendida, la poesía.

ISBN: 978-958-5589-07-0. 1° Edición 2020. 88 págs. Rústica. 15×23 cm. COP $30.000, USD 11

http://www.uniediciones.com/index.php/es/about-alias/en-el-umbral-detail

da Monica Guerra | Mar 13, 2018 | altre pubblicazioni

clicca qui per leggere su Anterem

Da “Sulla soglia”, Samuele Editore, 2017

4 luglio 2016

la paura è un morire piano

calma piatta nella gola

un arto alla volta

l’acqua che sale.

25 giugno 2016

qui è un filare anche il carezzare

tra ferite allineate

che non sono trama di parole

o la danza dell’ossigeno

che misura le presenze.

22 giugno 2016

grida distanza la valigia chiusa

sentieri stellari dietro lo spigolo quotidiano

perché morire

è solo vivere a rovescio.

***

vivere a prova di qualunque

garanzia – morire

sgombra tutte le stanze

da Monica Guerra | Feb 17, 2016 | antologie

Non voglio essere l’ultimo a mangiarti – antologia di poesie erotiche

Irina liquefatta

danza nella pioggia.

Riflessi

milioni di cani verdi

echi sbavati

di latrati languidi

pozzanghere di mani

nel fiume tra le cosce.

Monica Guerra

Leggi di più

da Monica Guerra | Lug 29, 2019 | antologie

100 Grandi Poesie Indiane (edizioni Efesto, 2019)

a cura di Abhay Kumar

Un’iniziativa unica di Abhay K. per portare la poesia indiana nel mondo, 100 grandi poesie indiane, proprio come l’India stessa, unisce i confini. Ti immerge negli scenari, nei suoni e nella filosofia del subcontinente e ti porta su un multiforme, lungo viaggio attraverso 3000 anni di poesia indiana in 28 lingue.

Calmati

— Anonimo

Occupato ora con il mio prezioso flauto di bambù,

le mie dita delicate sui fori.

Tesoro, non posso coccolarti ora,

sono perso nel suonare questo melodioso flauto.

Calmati – mangia un po’ di chilli!

Non posso stringerti proprio adesso.

Occupato con il mio piccolo prezioso flauto di bambù,

le mie dita delicate sui fori.

(Traduzione italiana di Monica Guerra dalla versione inglese)

Traduttori:

Alessandra Carnovale, Caterina Davinio, Chiara Borghi, Ivano Mugnaini, Laura Corraducci, Luca Benassi, Monica Guerra, Saverio Bafaro, Simone Zafferani, Tiziana Colusso.

En el umbral (Uniediciones, 2019)

En el umbral (Uniediciones, 2019)